Section Two Part 1: John Vann and the Principal People

by Jim Farmer

Jims-email@hotmail.com

February 15th, 2016 – June 4th, 2019

My Eyes loves to see the white People for what is it we can make of ourselves. – Raven of Hiwassee

For my Mom,

Mazell Childress Farmer.

- Cherokee packman, trader, and Indian countryman within the Hiwassee Valley Towns, Blue Ridge Mountains

- Indian trader at Ninety Six, Saluda River, South Carolina

- Captain for South Carolina, delivering goods to the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations

- Trader at the confluence of the Broad and Savannah Rivers, in Georgia, for the Cherokee Nation

- Captain of St. Paul’s Parish troop of Georgia Rangers

- Commissioner of Justice and Esquire for Hanover District, St. Paul’s Parish, Georgia

Outline of John Vann’s Family and Associates

Fig. 1 - South Carolina map showing the stretch of land from Ninety Six to the Broad River in Georgia, both places John Vann had trading posts and the path between them originally named after him.[1]

John Vann, Trader in the Cherokee Nation, Captain of the Georgia Rangers, St. Paul’s Parish

Born c1700-1710, near Somerton, Nansemond County, VirginiaSon of John Vann and Ann (last name unknown), who lived in Chowan District, North Carolina

Died after 1760, Pistol Creek, fork of the Broad and Savannah Rivers, Colonial Georgia

1st Wife: Mrs. Roe, Cherokee name unknown, daughter of the Raven of Hiwassee

Born c1720, Hiwassee Valley Towns, Cherokee Nation, Blue Ridge MountainsMember of the Wild Potato Clan

Died after 1798, Racoon Creek, Etowah, Cherokee Nation, Georgia

Daughter of a woman of the Wild Potato Clan and the Raven or Colona of Hiwassee and the Valley Towns

Sister of Skiakow (or Skienah, the Pigeon), and Moytoy of Hiwassee, two sons of the Raven of Hiwassee

Half-sister of Jenny and possibly James Dougherty, children of Cornelius Dougherty

Half-sister to Ogosotah (also called Sour Mush or John Greenwood) or his wife

o

Wife’s 2nd Husband: Bernard Hughes,

Cherokee trader

Their children:

§

Charles Hughes, killed by his nephew James Vann

§

James Hughes

§

Sarah Hughes, married Colonel Thomas Waters, British

soldier and Cherokee trader

o

Wife’s 3rd Husband: (Walter?) Roe

Their children:

§

David Roe

§

Richard Roe

Son: John Vann, Jr., aka Cherokee John Vann

Born

c1735 Hiwassee Town, Hiwassee Valley, Cherokee Nation

Died after 1806, Limestone (now Euharlee) Creek, Etowah, Cherokee Nation,

Georgia

His 1st wife: daughter of John Bryan and wife ___ Bunch

Their children:

§

Daughter: name unknown, married Colonel Thomas Waters

§

Son: John U-Wha-Ni Vann marred Polly,

daughter of Terrapin

(His

children were excluded from the Cherokee Nation because his mother, daughter of

John Bryan, was of African descent.)

His 2nd

wife: Agnes Weatherford, lived at Long Island, Holston River, Cherokee Nation,

Tennessee

Their children:

§

John Weatherford Vann

§

Keziah Vann, married Martin Maney

Daughter: Wahli, also called Mary or Mother Vann, baptized 1819 as “Christiana”

Born c1740

Hiwassee Town, Hiwassee Valley, Cherokee Territory

Died after

1821, Springplace, Connasauga River, Cherokee Nation, Georgia

Member

of the Wild Potato Clan

Her 1st

husband: Joseph John Vann, Cherokee trader and interpreter, nephew of her

father. (Presumably named after Captain Joseph John Alston, of Chowan, North

Carolina.)

Their Children

§

James Vann, Chief, of Springplace, Cherokee

Nation, Georgia

§

Jennie Vann, married James Brown, John Thompson

§

Nancy Vann, married John Fowling, George Harlan,

and others

Her 2nd

Husband: Clement Vann, brother to her first husband

John Vann’s 2nd wife: name unknown

Mentioned in

1751, Ninety Six Trading Post

Other family members and associates of John Vann

·

James Millican and Henry Augustin (Gustin), Bertie

Precinct, North Carolina 1728; Cherokee traders at Great Tellico 1725

·

Cornelius Dougherty, Cherokee trader since 1729

in the Hiwassee Valley towns and later a husband to Mrs. Roe’s mother

·

Ostenaco, designated as Otacite or

“Mankiller,” resided 1741-1751 at Great Tellico, called Captain Caesar of Tellico in

1751; resided 1756 at Tomatley and at Chota in 1763

·

James Maxwell, Charleston merchant and Cherokee

trader; Dougherty associate in land deal; employed John Vann to deliver trade goods

to the Choctaw

·

John Bryan/Bryant, planter and Cherokee trader at

Tomassee in 1751, father-in-law to John Vann’s son

·

Bernard Hughes, Indian trader at Stecoe 1751, and

Chewee 1754; second husband of Vann’s wife

·

Robert Goudey, Cherokee trader at Tellico 1751, merchant

at Ninety Six, and plaintiff in a lawsuit against John Vann and Dougherty in 1758

·

Avery Vann, brother with John Vann, found in

Ninety Six in 1751 before brother Edward

·

John Watts, Ninety-Six trader and Cherokee

interpreter for Georgia after John Vann

·

Edward Vann, John Vann’s brother, arrived in South

Carolina in 1758, father of Joseph John and Clement Vann, the brothers who

married John Vann’s daughter Wahli

Vann

·

John Stuart, British Indian agent for the

southern tribes

·

Samuel Chew, Lieutenant with John Vann in

Georgia Rangers, also an Indian trader

·

Bryan Ward, Cherokee trader and neighbor on

Broad River, Georgia, 1758

·

Charles Weatherford, Georgia, neighbor at Broad

River, Georgia 1758

·

Ezekiel Harlan, Georgia neighbor at Broad River,

Georgia 1758

·

Thomas Waters, Lieutenant in the Georgia

Rangers, Indian trader, and husband of John Vann’s granddaughter and step-daughter.

1710 John Vann Born near Somerton, Virginia

Fig. 2 - Map of Chowan Precinct, North Carolina, showing Somerton, just across the border in Nansemond County, Virginia.[2]

John Vann was born in Nansemond County, colonial Virginia, shortly before Virginia and North Carolina settled on a dividing line. In 1715, colonial governors Spotswood of Virginia and Eden of North Carolina decided upon the salient points of the boundary, agreeing that the line should begin on the north side of the Currituck Inlet and run "Due West" from there. This placed some of the Vanns north in Virginia and some south in North Carolina. The original homeplace, where John was born stayed in Nansemond County, Virginia, near Somerton (spelled “Summerton” on the map). Since two of the three sons of John Vann’s grandfather, William Vann, left wills in North Carolina, this suggests that the third son, John Vann’s father, also named John, remained in Nansemond County, Virginia, where the records are destroyed.

Fig. 3 - 1720 deerskin map of the Indian Nations in the Carolinas. Made by a Cherokee leader for the new governor of the South Carolina colony.[3]

Most important to John Vann’s story, when he grew up near Somerton, much of the community was focused on the Indian trade. Especially since South Carolina deterred traders living outside of their colony from trading with the Catawba and Cherokee within their province, traders working near John Vann sought access to the Chickasaws, Creeks and Choctaw who resided beyond the reach of the South Carolina government. These so-called Chickasaw traders held land on the Virginia-North Carolina border at the Occaneechi Neck on the Morratuck River in Chowan Precinct. The Occaneechi Neck was where the ancient Indian Trading Path crossed the Morratuck (now called the Roanoke) River. Robert Lang was one of those traders and was one those traders who also eventually settled in South Carolina near Ninety Six where John Vann would also choose to establish a home. Besides Robert Lang, there were others who were in Chowan Precinct and then found later residing in South Carolina’s Backcountry near John Vann. The first association between each them started with them being neighbors along the Morratuck River in North Carolina.

Patent: Robert Long in Chowan Precinct, 1713 - 640 acres on Ocanichey Plains[4]

Patent Issued: 28 Jul 1713 - Give and Grant to Robt Long 640 acres lying in Chowan precinct on Ocanichey plain…on a Cypress Swamp John Councils corner …John Councils and William Braswells corner tree..Mathew Surdivants and Henry Jones line to … Ocanichy swamp

Fig. 4 – John Bryan’s Patent at Cypress Swamp

Patents: Chickasaw traders at Occaneechi Swamp[5]

1725None of the above Chickasaw traders have records that tie them directly to the early Cherokee trade, but there is one name found on a map near these traders that does. This person is James Millican or “J. Milliken” at “Quounikee” Creek, opposite Occaneechi Neck, marked as “Acanechy” Swamp. The map was created in 1733. The location of Millican’s property was given in a deed when he and Henry Augustin purchased it from Gideon Gibson and wife, Mary Brown.

Paul Bunch Bertie - 265 acres S. side of Morattock river Patent No. 227

…on same page:

Richard Jackson, - 150 a, beginning at a pine on Qunkee pocosan, Henry Simms corner,

Paul Bunch, - 265 a, N side of Qunkee pocosan, to Simms line, to Gideon Gibson line to Wilkens line

John Gibson, - 200 a, Qunkee pocosan, joining Henry Simms,

1727

Phillip Jackson Bertie - 321 acres S. side of Morattock river Patent No. 338

…on the same page:

John Scott, - S side, Quaiunkey Pocoson

John Gibson - 328 a John Low’s line, Jackson line, to swamp.

Barnaby McKnnie - 100 a Southwest of Morattock

John Bryan of said co., - 194, S side, Thomas Whitmell, Cypress Swamp

Fig. 5 - James Millican, Thomas Bryant and Barnaby McKinnie shown at Quaniquee Pocoson, Occaneechi Neck, Bertie Precinct.[6]

North Carolina Deed, Bertie County: Gideon Gibson to James Millican and Henry Augustin[7]

22 Oct.1728 - Gideon Gibson & wife Mary to James Millican & Henry Augustin for 15 pds. for 150 Ac on S/S Moratuck River "bounded according to will of William Brown, Gentleman, dec'd." Wts: Rich. Hainsworth, Michel McKinsey, Rich. Jackson. Nov. Crt, 1728 E Mashbourne, D.C/C [This land was left to Mary by her father William Brown by will dated 15 December 1718]

The Journal of George Chicken, 1725-1728[8]

Thursday the 15 day of July 1725 - Arrived here from Tuccaseegee Samuel Brown and John Hewet who I sent for by an Order of the 8th Instant. And having Examined the said Hewet in relation to his being among the Indians without my leave, I found that he was Employed by Mr. Marr and that after he had left the said Marrs Employ that James Millikin Indian Trader Employed him and gave him Orders to Trade by two Letters from the said Millikin which the said Hewet produced to me and having Considered the aforesd Information, I gave Orders to the said Hewet to Stay at Keewohee til the said Milikin Arrived here from the Catawbaws at which time I informed him I should give him further Orders.

Munday the 2d day of August 1725 - Came in this day from Kewohee Henry Guston and Ja : Millikin, Indian Traders.

Wednesday the 3d day of August 1725 - This Morning appeared before me Ja: Millikin and Henry Guston to Answer a Complt agt^ them pursuant to my Orders of the 18th of July last in Relation to their Employing one John Hewet for one whole Year in the Indian Trade without my leave or Lycence which I proved before them by Two Letters from them to the said Hewet, wherein they Charge him not to Trade in the presence of any White Man for fear of his being discovered. And the said Gustin and Millikin pleading that they Employed the said Hewet out of Charity and without any design of defrauding the Country or in Contempt of the Government and hoping that I would take their Case under Consideration and to Shew them as much favour as the Circumstance of the Case would Admitt of, and as would seem mett with me, Promiseing for the future to take care of any further Complt against them. And on Considering the above Complt I Ordered them to give me a Note for the Sum of Thirty pounds payable to the Country it being there due from the said Hewet who Traded for them a whole Year without any Lycence and they having given me their Note accordingly on Mr. Saml. Eveleigh Mercht I then dismist them of the Complt agt them giving them in Charge to take care for the future how they behaved themselv's, which they Promised to do.

Chowan Precinct Road Order, North Carolina[9]

Jan 1737 - Orderd that the following persons be appointed as a Jury to Lay out ye Roads from Bennets Creek Bridge to Meherrin Ferry (Vizt) Henry Guston, Jno. Vann, Thos. Norris, James Wilson, Andrew Ross, George Hughs, Wm. Daniel, Edmd. [Edwd.] Vann, Jno. Alston, Thos. Speight, George Williams. Michl. Goulding & make return at ye next court.

An Understanding of the Cherokee Peoples

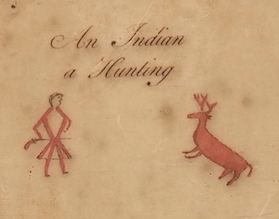

Fig. 6 - Cherokee hunter from the deerskin map.

The Ani-Yunwiya or Principle People, as the Cherokee call themselves, played an important role in John Vann’s life. He lived, worked and married into their world. During his lifetime, the Cherokee Nation included a number of town clusters defined physically be their environment. Each cluster of towns was scattered along those rivers and creeks carved out the valleys within the Blue Ridge Mountains. Each cluster of these valley towns entailed a sense of community built around strong family ties within and between the individual towns. Both location and family bonds united the people of these various settlements. Even the British and French colonial governments recognized the differences between the separate town clusters, often treating them as if they were independent states.

By tradition, the Cherokee referred to these settlements as if they were seven in number, much like their clan structure, which was made up of seven clans. In the time of John Vann, there were actually only five identifiable settlements. The list of those known included the Lower Towns, the Middle Towns, the Out Towns, the Overhill Towns, and the Valley Towns. For John Vann, the Valley Towns would be his home among the Cherokee.

About 1729, Sir Alexander Cuming kept a journal describing his travels among the Cherokees. In it he identified “mother towns” that governed the different settlements. Each mother town had an established town council house, which was the forum for headmen to communicate with their people and for the entire community to interact with each other. Cuming listed seven mother towns:

Fig. 7 - 1725

map updated by George Hunter in 1744 showing the towns in the Cherokee Nation..[10]

List of Mother Towns from Sir Alexander Cuming’s Journal[11]

The whole Cherrokee Nation is govern’d by seven Mother Towns, each of these Towns chuse a King to preside over them and their Dependants; he is elected out of certain Families, and they regard only the Descent by the Mother’s side. The Towns which chuse Kings, are Tannassie, Kettooah, Ustenary, Telliquo, Estootowie, Keyowee, Noyhee.An English census taken in 1721 of South Carolina mentioned five of the mother towns, although the spellings in the record are dissimilar to Cuming’s list. Anglican Reverend Francis Varnod prepared the report and sent it back to England along with the names and population for over 45 Cherokee towns. (One of Cuming’s towns, Ustenari (aka Ustenali) was not on the 1721 census list but it has been referred to as a mother town on the Tugaloo River in other records and may have been missed.)

Fig. 8 – Valley and Overhill Cherokee Towns in the Nation[12]

Cherokee Mother Towns in 1721[13]

Towns Men Wom’n Child’n District* and 7 Mother Towns List [*]

*Multiple towns have the same name in different districts making actual district locations difficult to assign.- 1. Kewokee 168 155 137 Lower Keyowee- 9. Eastotoe 150 191 281 Lower Estootowie- 12. Kittowah 143 98 47 Out Kettooah- 28. Nookassie 50 53 39 Middle Noyee (Nikwasi?)- 46. Terrequo, 100 125 116 Valley Telliquo

From the 1721 census, the English identified 10,434 Cherokee living in what was then called the Cherokee Mountains. This included 3510 men, 3641 women and 3283 children. Looking at Varnod’s list of town names, at least ten of them appear to be Valley Towns, but town names and locations changed over time. More than once, neighboring tribes, such as the Creek or Mohawk, attacked and ravaged Cherokee towns, often driving the Cherokee deeper into the mountains, deserting their homes, gardens, and corn fields for more secure places. Towns and their locations came and went accordingly.

A map of the nation drawn in 1725 describes the Cherokee Nation as divided into three settlement groups, not five. This is how the English most often viewed the Cherokee. On the map, the Valley Towns are on the left scattered along what today is called the Hiwassee River. The headwaters of the Hiwassee River begins at Unicoi Gap, Georgia, only a short distance from the source of the Chattahoochee River. It then flows northward down the slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains. On this map, the Hiwassee River is spelled “Euphassee.” The two names for the river and associated towns appear interchangeable in the records. Because this is where John Vann lived early on, tracking the Valley Towns is important to his history. The towns on the river and its tributaries are:

-

At the mouth of the Euphasee River: Chestoee,

Amoy, Euphassee

-

On the upper side of the Euphassee at the first

branch: Castoe,

-

Up the first branch: Tomatly

-

On the Euphasee above the first branch: Little

Euphassee

-

Up the second branch: Taskaye

-

On the upper side of the Euphasee above the

second branch: Tasheeche,

-

On the lower side of the (Little?) Euphassee Qanasseee,

Sequichee,

-

Up the last branch: Conacachi

None of these towns is listed as one of the seven

mother towns in Cuming’s list. The most likely town to be the mother town for

Hiwassee Valle would be Tellico, but it is not shown anywhere on the map. It is

possible that the ink has faded where it once was. A town with no label is

shown on a branch just right of the Euphassee River and could be Tellico on the

Tellico River. (A 1754 map of the “British Plantations” that looks like it was

derived from 1725 map includes “Taligwa,” but it places the town between

Chestoee and Amoy.[14]The 1721 census gives the following populations for the Valley Towns as identified on the map.

Francis Varnod’s 1721 Census of Colonial South Carolina[15]

Census of the Cherokee in 1721 - South Carolina, Dorchester1 April 1723-4 - A true & Exact account of the Number of Names of all the Towns belonging to the Cherrikee Nation & the Number of Men Women & Children Inhabiting the same taken Anno 1721.

-

21. Taseetchie 36 44 45

-

22. Quannisee 37 31 36

-

23. Tookarechga 60 50 45

-

24. Stickoce 42 30 30

-

…

-

38. Cheowee 30

42 42

-

39. Tomotly 124 130 103

-

41. Little Terrequo 50 56 48

-

42. Suigella 50 65 60

-

43. Little Euphusee 70 125 54

-

44. Little Tunnisee 12 30 20

-

45. Great Euphusee 70 72 60

-

46. Terrequo 100 125 116

While the actual number of towns in a settlement often varied in number, the Cherokee usually referred to the number within a settlement as being seven. This did not mean the actual physical count of the towns was seven. As stated before, instead, this reflected the relationship between their towns and their clan system. “Seven” described their community in all of its facets and at all levels.

Within a settlement, each household identified with one of seven clans and this identification stretched beyond individual towns. Modern names of the seven clans today are : a-ni-gi-lo-hi (Long Hair), a-ni-sa-ho-ni (Blue), a-ni-wa-ya (Wolf), a-ni-go-te-ge-wi (Wild Potato), a-ni-a-wi (Deer), a-ni-tsi-s-qua (Bird), and a-ni-wo-di (Paint).

Each household when identified with one of the seven clans depended on the identity of its women and their maternal connection, no matter what town or settlement they lived in. The Wild Potato Clan was the one associated with John Vann’ family for generations to come. (The name “wild potato” refers to apios amerciana, sometimes called the American groundnut, which provided natives across the colonies with edible beans and large edible tubers, as well as, medicinal uses.)

Within each large town, whether a mother town or not, stood a circular townhouse where civic and religious events took center stage. Lieutenant Henry Timberlake, who sojourned among the Cherokee, described the townhouses he saw:

Town House Description by Timberlake[16]

The town-house, in which are transacted all public business and diversions, is raised with wood, and covered over with earth, and has all the appearance of a small mountain at a little distance. It is built in the form of a sugar loaf, and large enough to contain 500 persons, but extremely dark, having, besides the door, which is so narrow that but one at a time can pass, and that after much winding and turning, but one small aperture to let the smoak out, which is so ill contrived, that most of it settles in the roof of the house. Within it has the appearance of an ancient amphitheatre, the seats being raised one above another, leaving an area in the middle, in the center of which stands the fire; the seats of the head warriors are nearest it.It was up to each town and settlement to choose its leaders and this was done within the townhouse. Each leader was selected to hold a position covering either civic or religious matters but these separated in responsibility between those supporting war (the “Red” leaders) versus those supporting peace (the “White” leaders). Lieutenant Henry Timberlake also described some of the titles given to the war leaders:

Fig. 9 - Ostenaco, an Outacite of the Cherokee Indians.

Cherokee Titles as described by Timberlake[17]

The rest of the people are divided into two military classes, warriors and fighting men, which last are the plebeians, who have not distinguished themselves enough to be admitted into the rank of warriors. There are some honorary titles among them, conferred in reward of great actions; the first of which is Outacity, or Man-killer; and the second Colona, or the Raven. Old warriors likewise or war-women, who can no longer go to war, but have distinguished themselves in their younger days, have the title of Beloved.

Other

War Names

Skyagunsta

- a head warrior

Conostocheskioe

- a bold warrior

Skaleloske

- a second warrior

Beloved

Names

Ouka

or Ukka - head king

Ounista

- king

Ketagunsta

– prince

Adawehi

- Conjurer

Identifying individual Cherokee leaders throughout their lifetime often depends on knowing the individual’s title and town to which they belonged, but for all Cherokee, both title and town changed over time. Within John Vann’s Cherokee family, the most important person was the Raven of Hiwassee. As will be shown, he was the father of John Vann’s wife. In a treaty written in 1751, where he signed and acknowledge the treaty with his mark, his title was given: “Corane, the Raven, King of the Valey, commonly called Tacite, the Man Killer of Hywassee.” It listed both his Cherokee title and an English translation. The Raven’s personal Cherokee names are not known.

Fig. 10 - Cherokees going to London, left to right: #7

Onaconoa, #2 Prince Ketagistah, #5 Kollannah, #1 King Ouka Ulah, #3 Tatutowe,

#4 Clogoittah, #6 UUkwanneequa (Attakullakulla).

In 1727, Colonel John Herbert, South Carolina’s Indian Commissioner, traveled up the Cherokee Path from Charleston into the Cherokee Nation where he met a headman from the Valley Towns called the “Conjuror of Ufassey” (i.e., Euphassee).

Journal of Colonel John Herbert description of Valley chiefs.[18]

Friday the 24th day of Novr. 1727 - [In answer to questions by Col. Herbert about the Creek Indians.]

That the Conjuror of Ufassey on his return from the Creeks sent him [old Breaker Face] a message to inform him that the head man of the Oakfuskey town told him that the Lower Creeks were not wiling for a peace & particularly the Cussetaw town who were resolved to have satisfaction for the people killed there by our people, and that if the Lower people would not make a peace that they would remove & settle somewhere near the Cherokee Towns—Later in the record, while he visited Tassachey, also a Valley Town, Colonel Herbert spoke with another head warrior who was named “Choa:tee:hee” of Great Tellico.

Journal of Colonel John Herbert names additional Valley chiefs.[19]

Saturday the 10th day of Febry. 1727[1728] - Sent the following Letter to his Honr. The President

May it please yr. Honr. - It happened to be on my return from over the hills before I rec’d your Honrs. Letter of the 16th Novr. Last wch occasion’d me to have a meeting with the Conjuror of Iwassey who was lately down with the Long Warriour, & several other head men at a town called Tassachey where I (pursuant to your Honrs. letter) asked them if they would assist us against the lower Creeks. … There hath lately returned from Warr a party of the upper people of a town called great Telliquo who have been out against the French Indians & have killed Six and brought in three Slaves, ‘tho they have come off with the Loss of two men this will I hope put an end to the peace…

Friday the 23rd day of Febry 1727 [1728] - Choa:te:hee one of the head Warriours of great Tellico (having on his return from Warr) heard that I enquired after him when I was at his Town came down to me some few days agoe at Keewohee, and according to his desire I had the talk interpreted to him wch I had with the people of his Town at a meeting at Tunnissey, To whch he gave thanks & assured me that he would soon return home & would set away in a short time from little Ufassey with a party of people that Town to Warr agains the lower Creeks—

Choa:tee:he [sic] with the head men of Keewohee mett this evening in the Town house & having sent for me the sd. Choa:tee:he (being Speaksman) discoursed me in the following manner—

…We think it wou’d be best for you to meet the head men of the Nation at Nequisey— …We think it better for us to go in a body against the Creeks than in parties, for parties of our people will only alarm them & give them an Opportunity to go away, & it may happen that they may kill our people if We go in parties— …Choa:tee:he still insisted on a meeting & finding that I would not come into his measures, told me that he was never at Warr with me & that he wanted me to go to Warr with him— …He answer’d that they had no Am’unition to go war with & desired to know if I would give them any— …He then insisted that I had not told him the talk he had heard from the upper people by wch. He understood that the English & they were to go to Warr together & that the time was appointed for their setting away & that he believed the English were afraid of the Creeks— Choa:tee:he hearing that I Was going this morning to Toogelo parts came to take his leave of me & told me not to mind what he say’d to me last night in the town house & that he shou’d perform his promise to me in going to Warr against the lower Creeks, but that he believed none of the lower people would go.It is evident from the above conversation that the headmen of Hiwassee and Tellico preferred to work with the English and not the French. This would be the viewpoint that the Raven of Hiwassee and Ostenaco of Great Tellico espoused for many years. However, the identities of Choa:tee:hee of Great Tellico and the Conjurer of the Valley Towns are unknown. They may have been the same men called Moytoy and Jacob in Cuming’s report a year later. His journal is paraphrased below:

Cuming’s trip to Great Tellico in the Cherokee Nation in 1728.[20]

-

March 27, the party left Joree, passed through

Tamauchly, and thence to Tassetchee,

[a Valley Town] being 40 miles.

-

On the 28th of March Cuming was within 3 miles of

Beaver-dams, where he spent the night; Ludovick Grant, and his guide, William

Cooper, being with him.

-

March 29, … on the top of the high Ooneekaway

mountain, … to Telliquo is a descent of about 12 miles. They reached Telliquo

in the afternoon; saw the petrifying cave; a great many enemy's scalps brought

in and put upon poles at the warrior's doors; made a friend of the great

Moytoy, and Jacob the conjuror. Moytoy told Sir Alexander, that it was talked

among the several towns last year, that they intended to make him emperor over

the whole; but now it must be whatever Sir Alexander pleased.

-

March 30, leaving William Cooper at Great

Telliquo, to take care of his lame horse, Sir Alexander took with him only

Ludovick Grant to go to Great Tannassy, a town pleasantly situated on a branch

of the Mississippi, 16 miles from Great Talliquo. …Here Sir Alexander met with

Mr. Wiggan, the complete linguist; saw fifteen enemies' scalps brought in by

the Tannassy warriors; made a friend of the king of Tannassy, and made him do

homage to George II on his knee.

-

The same night returned to Great Telliquo; was

particularly distinguished by Moytoy in the Councilhouse; the Indians singing

and dancing about him, and stroked his head and body over with eagles' tails.

After this Moytoy and Jacob the conjuror decided to present Sir Alexander with

the crown of Tannassy.

-

From Telliquo he proceeded on March 31, with

Moytoy, Jacob the conjuror, the bearer of eagles' tails, and a throng of other

Indians, and lay in the woods at night between 20 and 30 miles distant.

-

April 1, they reached Tassetehee, above 30 miles

from their last encampment.

-

On the 3d of April, Sir Alexander was at

Telliquo with his company, which consisted of Eleazar Wiggan, Ludovick Grant,

Samuel Brown, William Cooper, Agnus Macpherson, Martin Kane, David Dowie,

George Hunter, George

Chicken, Lacklain Mackbain, Francis Baver, and Joseph Cooper, all

British subjects. Here, at this time and place, Moytoy was chosen emperor over the

whole Cherokee nation, and unlimited power was conferred upon him.

When John Vann was working among the Cherokee, Moytoy of Tellico was one of—if not the—most important chiefs among the leaders of the Cherokee. In “The Journal of Sir Alexander Cuming,” Cuming wrote:

“On March 29, 1729 … arrived at Great Telliquo, in the upper Settlements, 200 miles up from Keeakwee. Moytoy the head Warrior here, told him, that the Year before, the Nation design’d to have made him Head over all;”At this time, Tellico was probably the mother town of the Valley Towns, making Moytoy the leader of the Valley Towns. In the eyes of the English in Charleston, however, he became the “emperor” of the entire Cherokee Nation, even though the Cherokee had no such concept. Besides Moytoy, the two other headmen associated with the Valley Towns and Tellico were the Raven of Hiwassee and Ostenaco of Great Tellico. The English often made note of the Raven of Hiwassee as an important headman in the Valley. Captain George Haig included a comment about him on a map.

The importance of the Raven of the Valley[21]

Note: These river towns lye in a Valley, the King of which is call'd Coronee or the Raven his other name is Tassatee the ManKiller he has a great sway over the whole Nation and is a man of the best sense in it he is a firm friend to the EnglishJames Adair also held the Raven of Hiwassee in great respect. His spelling of Raven as “Quorinnah” reflects the pronunciation used by the Cherokee of the Lower Towns.

James Adair admired the Raven[22]

Carolina and Georgia remember Quorinnah, “the raven” of Huwhase-town; he was one of the most daring warrior of the whole nation , and by far the most intelligent, and this name, or war-appellative, admirable suited his well-known character. Though with all the Indian names, the raven is deemed an impure bird, yet they have a kind of sacred regard to it…At the death of Moytoy, the Raven and Ostenaco both became essential contacts for the colonial governments in maintaining good relations with the Cherokee. In addition, the later actions and decisions of the Raven of Hiwassee and Ostenaco of Tellico would continue to be important in John Vann’s life among the Cherokee.

Millikan and Dougherty and the English Factors

Fig. 11 - George Hunter’s map showing his journey up to the

Cherokee Nation and their villages – 1730. [23]

Several trading paths ran through the Cherokee nation. These included the Great Trading Path or Occaneechi Path that ran through North Carolina to Chowan Precinct and the Unicoi Path running south through the Nation before connecting to the Cherokee Path that led to Charleston. Both of these paths ran along much of the Hiwassee River where the Valley Towns were located. Another old path known as the Warrior Path ran from Great Hiwassee Town near the mouth of the river and then up the Conasauga Creek across to the Cherokee town of Great Tellico on the Tellico River. These trading paths were lines of communication for the Cherokee, used by warriors, traders and messengers, alike, ensuring Hiwassee towns remained in contact with much of the entire Cherokee Nation, including those Indian traders established within its boundaries. James Adair described the Indian trading business in his “History of the American Indians.”

A license to trade[24]

Formerly, each trader had a license for two towns, or villages; ... At my first setting out among them, a number of traders who lived contiguous to each other, joined through our various nations in different companies, and were generally men of worth: of course, they would have a living price for their goods, which they carried on horseback to the remote Indian countries, at very great expense.

The Indians settle themselves in towns or villages after an easy manner; the houses are not too close to incommode one another, nor too far distant for social defence. if the nation where the English traders reside, is at war with the French, or their red confederates, which is the same, their houses are built in the middle of the towns, if desired, on account of greater security. But if they are at peace with each other, both the Indians and the traders chuse to settle at a very convenient distance, for the sake of their live stock, especially the later for the Indian youth are as destructive to the pigs and poultry, as so many young wolves or foxes. Their parents now only give them ill names for such misconduct, calling them mad; but the mischievous and thievish, were formerly sure to be dry-scratched.

Most of the Indians have clean, neat, dwelling houses, whitewashed within and without…the Indians, as well as the traders, usually decorate their summer-houses with this favority white-wash—The former have likewise each a corn-house, fowl-house, and hot-house, or stove for winter; and so have the traders likewise separate store-houses for their goods, as well as to contain the proper remittances received in exchange.

The traders hot-houses are appropriated to their young-raising prolific family, and their well-pleased attendants, who are always as kindly treated as brethen; and their various buildings, are like towers in cities, beyond the common size of those of the Indians.

An Indian Traders Table of Rates - 1718[25]

A Table of Rates to barter by; viz; Quantity and Quality of Goods for Pounds of heavy drest Deer Skins. [26]

A

Gun

16

A Pound of Powder

1

Four pounds bullets or shot 1

A Pound red Lead

2

Filly Dints

1

Two

knives

1

One Pound Beads

3

Twenty-four Pipes

1

A broad

Hoe

3

A Yard double striped yard-wide cloth

3

A Halfthicks or Plains

Coat

14

A Ditto, not laced

12

A Yard of Plains of Halfthicks

2

A laced

Hat

3

A plain

Hat

2

A white Dufield Blanket

8

A blew or red Ditto, two yards 7

A course Iinnen, two Yards 3

A Gallon Rum

4

A Pound Vermillion, [and] two Pounds red Lead, mixed 20

A Yard course Dowered Calicoe

4

Three

yards broad scarlet Caddice gatering laced 4

One of the best records of those men trading among the Cherokee comes from the journal kept by Colonel George Chicken from 1725-1728. Colonel Chicken had been appointed by the South Carolina royal government to ensure the backcountry’s Indian commitments. This meant keeping the traders in line. Not only did his journal mention James Millikan and Henry Agustin, it also showed Cornelius Dougherty, an early trader among the Valley Towns. Dougherty married the Raven’s wife and mother of John Vann’s wife. Throughout their Indian trade business and along with their family connection, Cornelius Dougherty and John Vann remained connected throughout their lives. His earliest record is the Chicken journal:

The Journal of George Chicken, 1725-1728[27]

Sunday the 8th day of August 1725. - Sent Additional Instructions to Ja. Millikin, Andrew White and Eleazer Wigan Indian Traders debarring them from taking Raw Skines.

Tuesday the 24th day of August 1725 - We set away from Tuccarecho … we came to Tamusey…Issued out Order to Mr. Cornelius Dougherty, Wm. Cooper, Edward Kirk, John Neely and David Doway debarring them of taking Raw Skines.

Munday the 6th day of September 1725. - Memorand : That John Facey and Wm. Collins are Allowed as Packhorse Men to James Millikin Indian Trader, he having given an Order on Samuel Eveleigh Mercht in Charles Town payable to the Publick for the Sum of £20, it being required by Law for the Endorsement of the said Pack horse men.

Saturday the i8th day of September 1725. - This day was brought to me by one of Capt. Hattons Slaves the Young ffrench Fellow that was to have gone down to Charles Town with James Fulton Indian Trader but made his Escape from Keewhohee the Night before. We set away from Tamusey and came to Keewohee.

Munday the 20th day of September 1725. - Set away from hence William Hatton and Henry Guston / Indian Traders an Order for Savanna Town.

Wednesday the ijth of October 1725. - Came in this day from Savanna Town Capt. Wm. Hatton, Mr. Wm. Cooper, David Doway, Henry Guston and one Daniel Kearl, a Virginia Trader.

Given under my hand at Keewohee this 12th day of October 1725. - Came in here from Great Terriquo Ja: Millikin Indian Trader who Informed me that the person (who lately brought into the said Town two Womens Scalps) with Eight more were gone out to Warr agt the Upper Creeks and that they had been out Six dales and that they were to return in Twenty dales from their sitting out. He likewise gave us an Accot that their Conjurer had given them Assurance of Success.As noted above, James Millikin was a trader at Great Tellico in 1725. This town would most likely be John Vann’s first location in the Cherokee Nation.[28]

Given under my hand at Keewohee this 12th day of October 1725. - Came in here from Great Terriquo Ja: Millikin Indian TraderWhile John Vann may have first been employed by Millican or Gustin, by 1730 he more likely was working with Cornelius Dougherty. From the little found on Dougherty, we know he was the Indian trader in the Valley settlements and living in the town of Hiawassee and later Quanassee on the Hiwassee River at least by 1725. George Chicken never made it to Dougherty’s town in his travels into the nation, stating that headmen from the upper settlements did not attend his talk, but he did send out an order to Dougherty to have him stop selling deer hides until he acquired a permit.

The Journal of George Chicken, 1725-1728[29]

Munday the 2d day of August 1725. - The head men of the following Towns being mett together at Tunisee I had the talk Interpreted to them.

- Tunissee . Terriquo . Tallassee Suittico . Coosaw .... Towns on this side the hills.

- Elejoy . Tamantley . . . Cheeowee Conustee .... Towns on the other side the hills.

- Towns wanting in the Upper Settlements: Iwasee and Little Terriquo

I inform'd them by the Two Linguisters that I was sent a great way by the English with their talk for the good of the Cherookees and hoped that they would take Notice of it. …And then I Examined them as follows in relation to the Coosaw [Upper Creek Town) Man being Rec’d by one of their Towns.

Q. Why did you not Immediatly send to your King living in the next Town to Yours and the rest of the people of your? …The Head Warriour of Great Terriquo made Answer … A. That he did send a Messinger and was going to send another but the News of Quannissee being Cutt off by the people of the Coosaw Man's Nation made him run away in the Night after four days Stay wth him.

Tuesday the 24th day of August 1725. - We set away from Tuccarecho about Eight of the Clock in the Morning and about five in the Evening we came to Tamusey being about 25 Miles where we lay all Night. Issued Out Orders to Mr. Cornelius Dougherty, Wm. Cooper, Edward Kirk, John Neely and David Doway debarring them of taking Raw Skines.The Cherokee village of Quanassee sat at the headwaters of the Hiwassee, where the trading paths came together before trailing down into the Valley. It would later be the location of Cornelius Dougherty’s trading post or “factory” but in 1725, Creek Indians attacked the town and its people so its people had to resettle elsewhere.

Fig. 12 - The English “Factory” at Quanessee and another at Great Tellico.[30]

Public trading factory established in 1717[31]

… In 1717, South Carolina established a public trading "factory" (store and warehouse) at Quanassee to supply the region with English manufactured goods in exchange for deerskins and other Cherokee commodities. … in 1725, a Coosa (Creek) war party "cut off" Quanassee, destroying the town and killing or enslaving most of its inhabitantsAs shown in English reports in 1751, Cornelius Dougherty was most often called a trader at Hiwassee. He apparently never left the Cherokee Nation. As late as 1797, sometime after his death, he was mentioned as the old trader who had lived at Quanassee at the head of the Hiwassee River.

Cornelius Dougherty at Quanasee[32]

Colonel Benjamin Hawkins…in an account of a trip…on March 23, 1797 - …the party encamped by the Hiwassee, …The Colonel goes on to say the former site of Quanasee was on the left side of the river. He notes that nothing remained of the settlement…this writer believes, it was just to the south of the town of Hiawassee…Colonel Hawkins gives no further details about Quanasee except to comment that the place was the residence for many years of an Irish trader named … Cornelius Dougherty… Dougherty claimed in an affidavit made at Charleston that he did not go to the Cherokee Nation till 1719.

1734 John Vann in Chowan Precinct

From a single record, we know John Vann made a return trip to Chowan Precinct in 1734, when he was a witness for a deed for a neighbor, Abraham Odam. No doubt, John Vann had already been in Indian country working as a packman for either Millikan or Agustin and was on a return visit home.John Vann witness for Chowan County Deed[33]

Book D, p 196 Abraham Odam of Chowan Precinct to Walter Brown

May 14. 1734. 10 pds. for 100 acres on South side of Cutawitsky Meadow at mouth of Long Branch adjacent Bryan O’Quin. Wit: James Barnes, John Vann, Junr. May Court 1735. John Wynns, Deputy Clerk of Court.The “Junior” is how we know this to be John Vann and not his father John who lived in the area. Abraham Odum, the grantor in the deed, married Sybil Barnes, the sister of Mary Barnes who had married Edward Vann, John’s brother. Bryan O’Quin was a neighbor who at one time lived near John Vann’s parent’s property at Cypress Swamp in Nansemond County, Virginia.

1735 John Vann’s Hiwassee Family

When John Vann returned to the Cherokee Nation from Chowan, North Carolina, he took a Cherokee wife. Later in life, she was called “Mrs. Roe,” retaining the name of her last husband. The year of her marriage to John Vann and the birth of their son John Vann was about 1735. The time frame suggests they married when she was living in her mother’s household, a member of the Wild Potato clan, in Hiwassee Town. This location is most likely because Cornelius Daugherty was the Indian trader from Hiwassee and had married the mother of Mrs. Roe. Being from Hiwassee Town also makes sense if Mrs. Roe was the daughter of the Raven of Hiwassee.Cornelius Dougherty’s own daughter Jenny was a half-sister to Mrs. Roe according to in the Moravian Journals chronicling much of the Vanns’ lives later in Georgia.[34] Therefore, this connection and Cornelius Dougherty’s on-going association with the Raven of Hiwassee provides the best proof that Mrs. Roe was the Raven’s daughter. (No original source has been found showing her to be “a sister of Raven,” as is often mentioned online.) Dougherty’s trading post or “factory” at Hiwassee was still there in 1751 along with the Raven.

Affidavit of James Maxwell June 12th, 1751[35]

The Deponent then proceeded over the Mountains to the Valley, and went there to Hywassee to Corns. Dougherty’s House, a principal Trader there. He said all was well and that the Raven of Hywasse, Head Man of 7 Towns, would not hear any bad Talks, though there had been frequently many sent from the Lower Towns. At the Place the Deponent met with Robert Gandey [sic, s/b Goudey] and Saml. Benn, 2 principal Traders over the Hills, and asked them what news there. They told that all seemed to be well there…As mentioned before, another location for Dougherty was the small village of Quanassee at the head of the Hiwassee River. Quanassee, one of Dougherty’s long-time trading sites in the Hiwassee Valley later on was also under the authority of the Raven.

The Moravian records show that Mrs. Roe had also married Bernard Hughes.[36] Because of this relationship, the following deposition of an attempted attack on Hughes further suggests the connection to the Raven. The Indian woman mentioned is considered to be Mrs. Roe. She came to Hughes’ rescue and warned him of the danger before running to alarm the Raven of Hughes’ situation. As a consequence, it was by the Raven’s authority that Hughes was protected. He reprimanded the rogue Indians and ordered them to return the stolen supplies to Hughes. He would also send his own sons to punish the Indians involved.

Bernard Hughes’ rescue described in the James Maxwell deposition[37]

… The 27th [day of April] it rained very heard [sic] most of the Day,, … but about 5 o’Clock I saw one James May and two of his Men coming to the House very fast on Foot, who told me there was very bad News. That an Indian Woman was come to their House and said that the Cherokees and Norwards on Tokasigia River actually killed Danl. Murphey, and that they went to kill on Bernard Hughs and his Men and take his Goods, but that she ran to tell him of it, but that he was very slow to run off and the Indians came and broke open his Store and took all his Goods and Leather, and parted it among them, and sent Parties after Hughs and his Men to kill them, which I am afraid they effected.Dougherty continued to associate with the Raven’s sons even after the Raven’s death. One son of the Raven, named Moytoy, stood up against his brother for Dougherty’s sake, suggesting that the Raven’s son and Dougherty’s wife were members of the same maternal clan. While Dougherty’s wife could have been Raven’s sister, the support Raven’s son Moytoy gives Dougherty after Raven’s death suggests otherwise.

From her marriage to Bernard Hughes, Mrs. Roe had three children: Charles, Sarah and James. She would later marry a man named Roe. It is possible that he was Walter Roe, listed in a roster of Georgia Rangers. Vann relatives were also listed among the troop, but there are other Roes that could be her husband.

Captain Barnard and Lieutenant Thomas Waters’ Georgia Troop Roster[38]

Pay Bill of His Majesty’s Troops of Rangers doing duty in the ceded lands under command of Captain Edward Barnard, Sept. 6, 1773- to Mar 1774.

Rank

Name

Comments

Captain

Barnard, Edward

Comm. Sept 6, 1773

1st Lieut.

Waters, Thomas “

…

Rank Name

Comments

Private Roe, Walter

“ Vann, Joseph

enl. Feb 12, 1774

“ Vann,

Clem “

“ Vann,

Cader “

Her sons from this marriage were David and Richard Roe. In his journal in 1796, Agent Benjamin Hawkins explained Mrs. Roe’s relationship to two of her sons, John Vann, Jr., son of John Vann, and David Roe.

U.S. Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins, writing in December, 1796, Hawkins wrote:[39]

Sunday, 3rd Dec. - This morning the women recommended two men, a young one and an old man to conduct me to the Creeks. They brought them prepared to set out, and they said that as I should soon be in a situation not so secure as I had been with my horses, the old man determined to take me by the hand and see me safe. I sat out X the river about 80 yards wide, moving W. N. W. went down for half a mile, then left it W. and passed thro' some very level land, not rich, in 2 miles X a small creek, in 1 ½ come to John Van's & David Roe living on a creek 10 feet wide (Raccoon). John Van bargained with my two guides to conduct me for a blanket each. I paid them. The blankets were 3 dollars each. Here old Mrs. Roe, near 80, the mother of these men received me and treated me with great kindness.

1738 Smallpox among the Cherokee

In 1738, a smallpox epidemic decimated the

Cherokee Nation. The epidemic, which spread throughout the South Carolina colony

originated from a slave ship, the London Frigate, infecting more than two thousand of the

roughly six thousand people in Charleston. It killed more than three

hundred. Adair

wrote about its effect on the Cherokee in his “History of the American Indians”

where the death count was much worse.

The smallpox engulfs the Cherokee[40]

About the year 1738, the Cheerake received a most depopulating shock, by the small pox, which reduced them almost one half, in about a year’s time…and to them a strange disease, they were so deficient in proper skill, that they alternately applied a regimen of hot and cold things, to those who were infected. … A great many killed themselves; … seeing themselves disfigured, without hope of regaining their former beauty, some shot themselves, others cut their throats, some stabbed themselves with knives, and others with sharpened canes…James Maxwell, the Charleston merchant and Cherokee trader associated with John Vann and Cornelius Daugherty, also made a report on the decimation of the population of the Cherokee after the smallpox epidemic. The Cherokee appears to have lost over two thousand souls when compared to the population in 1721.

Maxwell report of the Cherokee population after the small pox epidemic[41]

… [the Cherokee] numbers and names,…furnished Lieutenant-Governor Bull in 1741, by the white Indian trader, James Maxwell; who had been sent to the nation by the Lieutenant-Governor. Mr. Maxwell says, “In the Cherokee Nation I find there is forty-seven towns; and from the best information I could get from the traders,There is about 2,000 - Gunmen.

And about 1,000 - Boys, from the years 12 to 15.

At least 4,000 - Women—also abundance of children.

Total 7,000 of the nation in 1741.

End of Part 1/3

[1] Henry Mouzon Map of North and South Carolina,

1775, Library of Congress, Call No. G3900 1775

.M6

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3900.ar139401/?r=0.057,0.352,0.375,0.176,0

[2] Jefferson-Fry Map of Virginia 1771, Library

of Congress, Call. No. G3880 1755 .F72.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3880.ct000370/?r=-0.229,-0.005,1.48,0.698,0

[3] The Catawba Deerskin Map 1720, Library of

Congress, Call No. G3860 1724 .M2 1929.

https://www.loc.gov/item/2005625337/?loclr=blogmap

[4] (State Archives of North Carolina, n.d.) MARS: 12.14.46.958

File no.: 982

[5] (State

Archives of North Carolina, n.d.) P. Bunch MARS: 12.14.32.226; J. Bryan MARS:

12.14.32.341; et. al. http://www.nclandgrants.com/

[6] (Joyner

Library)

New and Correct Map of the Province of North Carolina,” Date: 1733 | Identifier: MC0017, http://www.ecu.edu/cs-lib/giving/maps.cfm

[7] Bertie County Deeds,

http://www.oocities.org/ourmelungeons/gibsontl.html

[8] (Chicken, 1916, p. 132) http://libsysdigi.library.illinois.edu/oca/Books2008-06/travelsinamerica00mere/travelsinamerica00mere.pdf

[9] (Hathaway, 1900, p. 448)

[10] (Hargrett) http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/hmap/id:hmap1725h4

[12] (Hunter, 1917)

https://dc.statelibrary.sc.gov/bitstream/handle/10827/7842/DAH_George_Hunters_Map_of_Cherokee_Country_1917.pdf.

https://dc.statelibrary.sc.gov/bitstream/handle/10827/7842/DAH_George_Hunters_Map_of_Cherokee_Country_1917.pdf.

[13]

See Cumin’s List and 1721 Varnod Census.

[14]

(Hargrett)

https://www.libs.uga.edu/darchive/hargrett/maps/1754b6.jpg

[16] (Timberlake, 2007, p. 15)

[17] (Timberlake, 2007, p. 72)

[18] (Herbert, 1936, pp. 26-27)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001263870

[19] (Herbert, 1936, pp. 26-27)

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001263870

[20] (Waters, Vol 26)

https://www.werelate.org/wiki/Early_History_of_Georgia_and_Sir_Alexander_Cuming%27s_Embassy_to_the_Cherokees

https://www.werelate.org/wiki/Early_History_of_Georgia_and_Sir_Alexander_Cuming%27s_Embassy_to_the_Cherokees

[21] (Hunter, 1917)

[22] (Adair, 1980, p. 195)

[23] (Hunter, 1917)

[24] (Adair, 1980, pp. 394, 442-443)

[26]“Rae’s

Creek”, by Morgan R. Cook, Jr., Dept. of Anthropology, Georgia State Univ. 1990; (Original Source: Journal of the

Commissioner’s of Trade, 1710-1718.) See

http://waring.westga.edu/Publication/RaesCreek.PDF.

[29] (Chicken, 1916)

[30] North Carolina Historical

Mark HMS4G: Quanassee Town and the Spikebuck

Mound, Hayesville, NC

[31] https://www.historicalmarkerproject.com/markers/HMS4G_quanassee-town-and-the-spikebuck-mound_Hayesville-NC.html

[32] (Goff, 1975, pp. 63,65-66)

[33] Chowan County Deeds (Human-Kirkland)

[34] (McClinton, The Moravian Springplace Mission to the

Cherokees Volume II – 1814—1821, p. 280)

[35] (McDowell, 1958, pp. 68-71)

[36] (McClinton, The Moravian Springplace Mission to the

Cherokees, Volume 1 – 1805—1813, p. 125)

[37] (McDowell, 1958, p. 117)

[38] (Davis, 2000, p. 39)

[39]

National Archives Microfilm 234, Letters

received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1831, reel 73, Cherokee Agency

East, 1824-36, letters for the year 1829.

http://trailofthetrail.blogspot.com/2011/11/euharlee-ga-taking-care-of-red-people.html

[41] (Drayton, 1821, p. 408)

Great info. I have a Rebecca ( Vann ) who m. Capt. David Gwynne. They're my 6th GGP's. She was b. 1764 & d. 1853. I have matches with Starr/ Vann/ Burleson/ Maney/ Hicks and others on DNA hits at Gedmatch, 23&Me, as well as FTDNA.Not sure where my Rebecca fits in here. Help?

ReplyDeletehttp://www.southern-style.com/powhatan_vann.htm

Deletehttps://sites.google.com/view/keziah-vann-cherokee/home/timeline

This should help clear it up a for you. Rebecca is keziahs sister